For the last two decades, urban growth in the MCMA has been driven by large housing developments on the periphery of the metropolitan area, encouraged by federal housing policy. That policy aimed to maximize housing supply, which was accomplished by expanding developers’ access to government-subsidized housing finance (Monkkonen, 2011). Formal workers in Mexico (defined as those with salaried tax-paying jobs), are eligible for federally subsidized mortgages. Since the final cost of the housing unit is an important criterion determining eligibility for subsidized credit, developers turned to cheap agricultural land to build large gated communities of thousands of monotonous single family dwelling units. This policy framework means that more housing is built, large-scale, on speculation by private companies rather than through a more traditional incremental building process where supply more closely follows demand (Monkkonen, 2011). Furthermore, access to the subsidized mortgages requires formal employment, such that those who do not have a formal job are often forced to rent or locate in low-quality, peripheral housing sometimes in originally self-built neighborhoods without adequate infrastructure.

While these policies succeeded in creating thousands of new housing units (for example, 675,000 loans were given nationwide in 2009 alone), they have had several adverse effects. For example, the resulting housing projects are distant from major employment centers and lack accessibility to most basic services. In 2010, the average commuting distance from the MCMA’s social housing units was an estimated 22 km (13.6 miles) (Montejano Escamilla et. al. 2016). As a result of their relative inaccessibility, many of these units are abandoned, and workers have stopped paying their mortgages (Monkkonen 2011). This, combined with a lack of basic services like policing, has led to high levels of crime and violence, making the neighborhoods even less attractive for workers, even they have no other chance of home ownership. One result has been a severe imbalance in housing demand and supply. For example, in 2010, Mexico City had a very low vacancy rate (8%), while two State of Mexico municipalities that had been heavily impacted by this housing delivery policy had some of the highest percentages of unoccupied housing nationwide: Huehuetoca (44.7%) and Zumpango (39.7%) (OECD, 2015). Additional problems include increased economic segregation and inequities in travel burdens in the MCMA (Monkkonen 2011) and greater car dependency and higher overall transportation costs for residents (Guerra 2015).

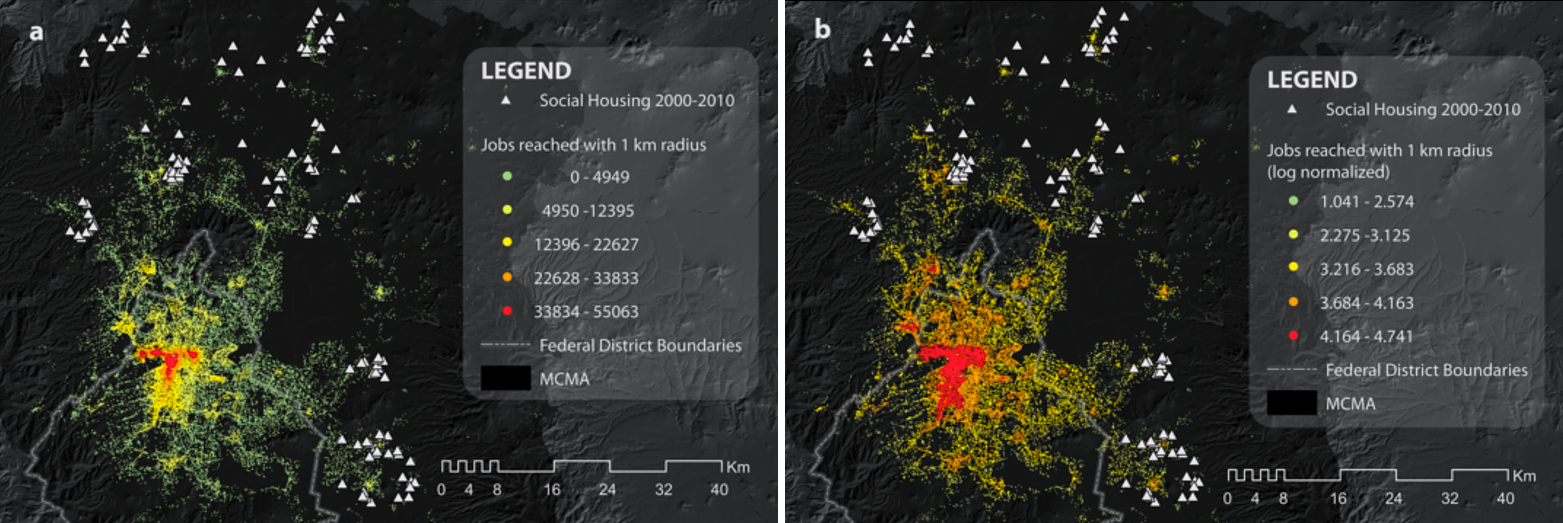

Location of new developments and concentration of formal jobs (Montejano Escamilla et al. 2016)